I’m really excited about the course I’m teaching this semester. DIKULT303: Digital Media Aesthetics is a graduate seminar with a topic that changes from year to year, and this year it will be about machine vision, my current obsession, and a topic I think is going to be immensely important over the next decades. The key question is: What happens to our understanding of the world when we no longer primarily rely on human perception but use machines and algorithms to sense our surroundings? We’ll be reading theory, learning about the history of visual technologies, and exploring digital art, literature, apps and games that engage with the question of machine vision.

UiB is switching to a self-hosted Canvas installation as an LMS, and I’ve been enjoying figuring out good ways to use it to craft a course design where learning activities, learning outcomes and assessment are well integrated. So if you’re curious, you can look at the syllabus or the modules to see how the course is structured. This lets you see the individual assignments, readings and lecture topics.

DIKULT303 is an MA level course primarily for students of Digital Culture at UiB, but also welcoming exchange students and MA- or PhD-level students from other programs at UiB. If you are interested in taking the course, sign up at Studentweb if you are a Digital Culture MA program, or email studieveileder@lle.uib.no if you are in a different program.

But you may be wondering what I even mean by machine vision? Here is a short introduction to the course topic.

We will begin the semester by learning about the history of visual technologies. We will visit the Maritime Museum to learn how vikings navigated by the stars and the sun even when they couldn’t see them, and how to use a sextant. We will learn about perspective in painting, camera obscuras, kaleidoscopes and early photography. We will discuss Rodin’s objection to the speed of the camera, and learn about the development of both photography and computers were to a great extent driven by a desire to identify each member of the population. We will discuss whether Google Street View or satellite images of the world change the way we see our surroundings. We’ll try out VR using Google Cardboard, and will discuss the theories of the New Aesthetic, reading work by Virilio, Uricchio, and others.

This is an example of a video showing us something that we cannot see without technology. It’s actually not a recording, but an animation based on scientific studies of the brain, first published at Art of the Cell, a medical animation company, but since reposted many places and often with the following text: “This is what happiness really looks like: Molecules of the protein myosin drag a ball of endorphins along an active filament into the inner part of the brain’s parietal cortex, which produces feelings of happiness.”

Part of the reason this image appeals to us is the anthropomorphic strut of that myosin – and the words that go with this image. “This is what happiness really looks like.” What do we mean by that? What it really looks like?

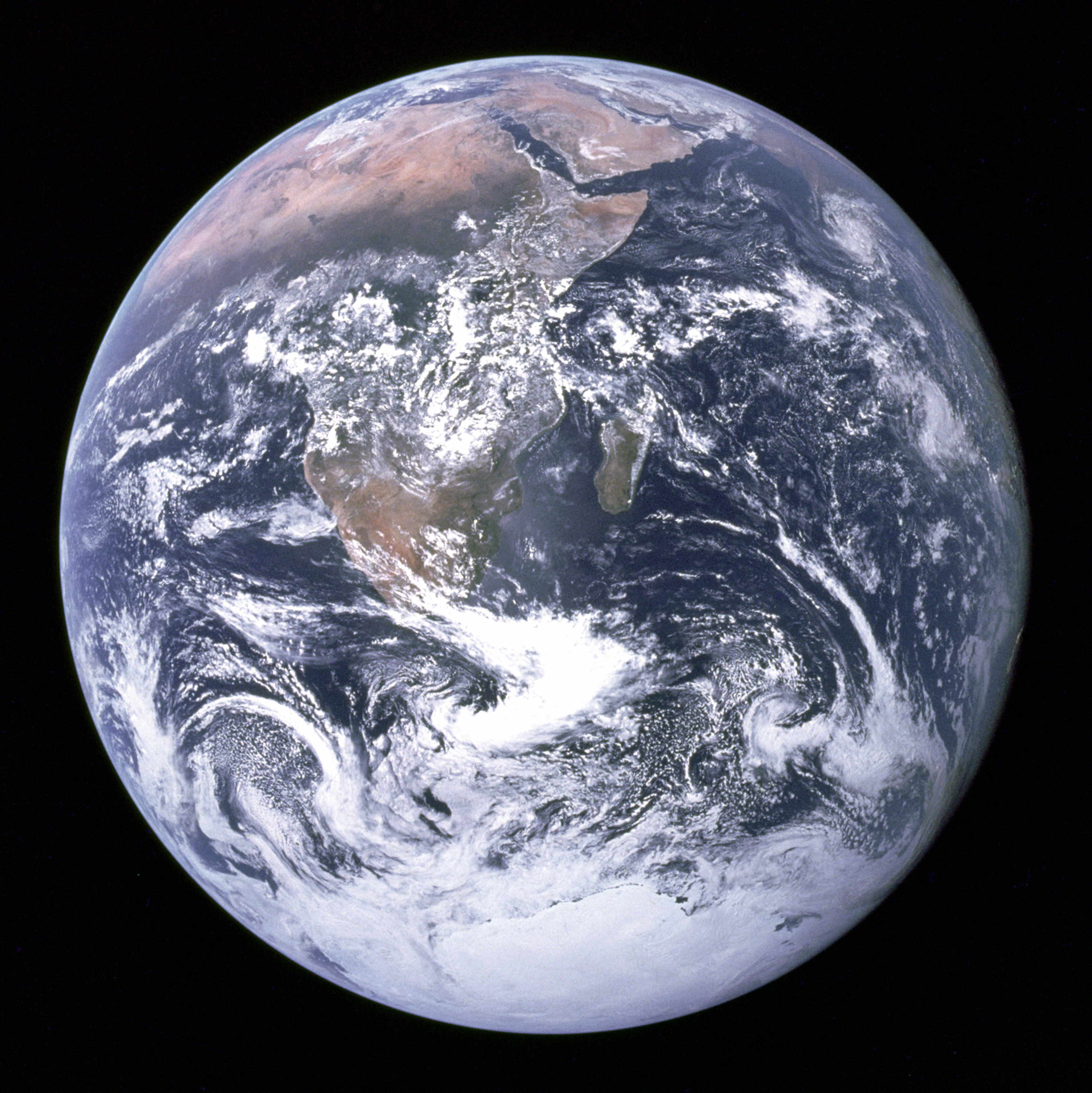

Consider the first photographs of an unborn child, popularised in the 1960s by Lennart Nilsson’s still popular book, A Child is Born. The photo below is a slightly updated version of one published in Life Magazine in April 1965 (This issue was digitized by Google Books so you can look at the cover here, and scroll through to page 54 for the whole story). To me, the child looks like a traveler in space, the specks like stars against the black of space. I immediate thought of the photos of the Earth, thinking they were taken about the same time, but of course, the iconic Blue Marble photo of Earth wasn’t taken until 1972.

Is this what an unborn child, or the Earth, really look like?

Leafing (well, scrolling digitally) through the issue of Life where Lennart Nilsson’s photos were published, I notice the spherical shape is repeated. First, on the page immediately after the section on the in-utero photographs, there is an ad for a car, where a fisheye view of what can be seen from the back seat of the car is shown, bright blue on a black background.

Then on page 83, which is a full page ad for Hughes and Comsat, showing a new satellite that will enable live trans-Atlantic telecasts and phonecalls. A globe is shown in the ad. Not a photograph of the Earth itself, because no photograph of the whole Earth yet existed. There seems to be a desire, though, for photographs of spheres floating in space.

The spherical image in the Ford ad was clearly taken with a fisheye lens (Links to an external site.). Fisheye lenses weren’t mass-produced for photography until the early 1960s – so just before this issue of Life was published. Nilsson used fisheye and wide-angle lenses both for his photography inside the body and for other photographs. And he even presented images actually taken outside of the body – like that of a foetus taken from the womb of a woman who was killed in a traffic accident – as though they were taken with wide-angle lenses.

Read more about this:

Jülich, Solveig. 2015. Lennart Nilsson’s Fish-Eyes: A Photographic and Cultural History of Views from Below, Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journal of Art History (Links to an external site.), 84:2, 75-92, DOI: 10.1080/00233609.2015.1031695

(You will have to either be on the UiB network or use a VPN to access the article.)

Related

Discover more from Jill Walker Rettberg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.