A woman applying to the Norwegian Research Council’s program SAMKUL only has half the chance a man has of being supported.

36% of projects funded by the Norwegian Research Council last week are led by women. That’s great, you might be thinking. Sure, it’s a pity more women don’t apply, but 36% isn’t too bad.

What if I tell you that over half the applicants to this funding program were women? That’s not all: over half of the very best projects according to the external review panels were led by women. And yet only 4 of the 11 funded projects are led by women. What happened?

The program I’m talking about is SAMKUL: Cultural Conditions Underlying Societal Change. SAMKUL is one of the Research Council’s thematic programs. While the free programs award funding based on scientific quality alone, thematic programs are designed to encourage research on topics society needs, so the selection is based on relevance to the call in addition to the quality of the project. External review panels assess the quality, then the program committee prioritises the best projects according to their relevance to the call. In practice, the advisor at the Research Council told me, this means they consider all the applications that received the two best grades from the review panels, so all the 6s and 7s. This year, that group consisted of applications from 13 women and 12 men.

I was one of the many researchers whose application was rejected. Nothing unusual about that, I thought, until I read the assessment. Wow! I got the top grade, a 7! The reviewers loved my application! But the program committee thought my project “had too little focus on cultural conditions and this weakened the project’s relevance to the SAMKUL program”. That was the only reason I received for the rejection. Seven of us got the top grade. I was the only one of the seven not to be funded.

Oh well, maybe I messed up on relevance, I thought. Applying for research funding is like buying a lottery ticket, I’ll just try again next year, I thought. But then I started asking the advisor at the Research Council about the numbers behind the grants, and I started to see a bigger picture. It is not a pretty picture.

You see, this isn’t the only year SAMKUL has given fewer women than men grants.

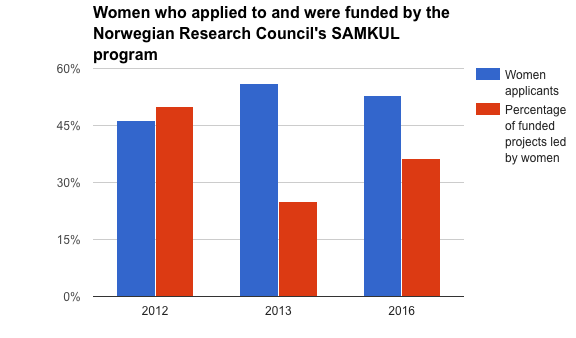

The last call, in 2013, was even worse. That year, 53% of the applicants were women, and only 25% of grants went to women! I fed the numbers the Research Council advisor I spoke to sent me into a spreadsheet. This is what I saw:

We researchers often talk about how hard it is to get research funding. Only 9% of applications to SAMKUL were funded this year, and 2013 was about the same. But women who applied had an even worse chance of receiving funding. Oh, in 2012 the gender balance was pretty even. But a woman who applied to SAMKUL in 2013 only had a 4% chance of receiving funding. A man who applied that year had a 15% chance of being funded. This year, women stood a 6% chance of being funded. Men had a 12% chance.

That means that this year, a man who applied to SAMKUL had twice the chance of being funded compared to a woman. And this is despite the fact that more women applied than men, and that there were more women than men among the 25 best applications.

Of course, the Norwegian Research Council has a policy that’s intended to improve the awful gender imbalance we have in research leadership. SAMKUL’s work plan for 2016–2020 also explicitly sets gender balance as a goal: “When selecting projects for funding in the future, the programme board will ensure that the gender balance among the project managers remains good.”

The call also states that moderate gender quotas will be used in the selection of projects: when a man and woman’s applications are assessed as essentially equal in quality and relevance, the woman’s project will be selected. The fact that men had twice the likelihood of getting funding this year suggests that the committee forgot about all these fine words about gender balance in research leadership. It’s really difficult to see how such a clear bias towards funding men could have happened, both in 2013 and in 2016, if someone in the meeting had simply asked, “Have we considered the gender balance? Are we assessing men and women equally?”

It’s surprising how few specifics the Research Council website and reports provide about gender distribution. These charts and figures are not from their website: I made them from numbers I requested from an advisor at the Research Council. If you want to see the details, here is the spreadsheet.

There is a midway report on SAMKUL published in 2015 which includes a section on gender balance, but it doesn’t include all the relevant information. It states that 10 of 24 projects (40%) funded in 2012 and 2013 were led by women, but doesn’t mention that this is due to the excellent gender balance in 2012, whereas the 2013 round only had 25% women project leaders. It also doesn’t mention that more than half the applicants over these two years were women, which you statistically should mean that at least half the funded projects would be led by women. Other criteria than gender are analysed in far more detail than this. For instance, sections 2.3.6 and 2.3.7 carefully examine the number of applicants from different institutions and disciplines and compare the number of applicants to the number of grants awarded to make sure that the distribution is fair. Why has this comparison not been made for gender? Perhaps because the Research Council wanted to hide the appalling imbalance in 2013, where male project leaders had over three times the likelihood of being funded as female project leaders did?

If this data had not been suppressed in the 2015 report, perhaps this year’s committee would have been more thoughtful in ensuring a gender balance in this year’s allocations.

The Research Council needs to make changes to ensure that this doesn’t happen again. Here are three steps they could take:

- Numbers showing the gender balance for applicants and awarded grants should be made public at the same time as the grant allocations are announced. Committees that allocate funding need to know that the gender balance, or imbalance, will be visible, and applicants need to know that the process was fair. It shouldn’t have been necessary for me to have to phone an advisor to get numbers showing the relationship between the gender of applicants and funded projects.

- Decision makers and advisors need training in implicit bias, so they know how it works and know how to work to avoid it.

- If the policy stated in the call is to use moderate gender quotas, then this should actually be used if it is necessary in order to achieve gender balance.

Fine words in reports and policy statements aren’t enough. The Research Council needs to examine its routines and assess whether SAMKUL has done what it was supposed to do. What happened in 2013 and 2016 cannot happen again.

It’s no use blaming the women this time. The extraordinary gender imbalance in SAMKUL’s project funding is obviously not caused by women not applying?—?more women applied than men. It is not caused by women’s’ research being worse than men’s’?—?the external panels found women’s’ projects to be as good as men’s. No, the numbers show that the problems lies with the program committee that prioritises men’s projects above women’s, with “relevance” as their excuse. That’s not good enough in 2016.

If you think gender balance in research is important, please share this on Twitter and Facebook so more people will read it, and research councils around the world reconsider their policies

Related

Discover more from Jill Walker Rettberg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.