I got a pile of books about the history of self-portraits at the UIC library yesterday, and I’m particularly enjoying Raynal Pellicer’s Photo Booth: The Art of the Automatic Portrait (Abrams, New York, 2010; translated from French by Antony Shugaar). There are so many similarities between the ways people experimented and played with early photo booths and the way we play with digital selfies today. Photobooths really made self-portraits accessible to the general public.

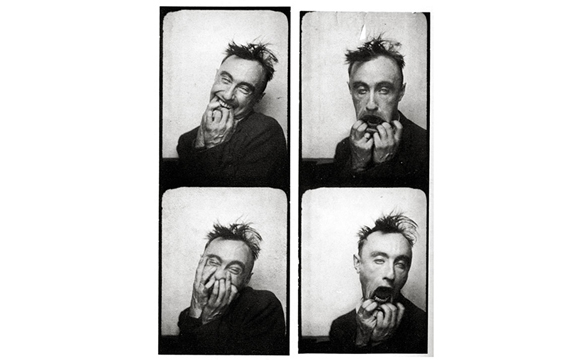

Did you know the surrealists loved them, too? Automatic photos – it’s like automatic writing, perfect surrealism! Here’s Yves Tanguy in the 1920s.

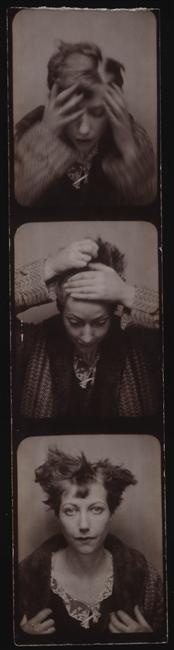

And here’s Marie-Berthe Aurenche:

And here’s Marie-Berthe Aurenche:

Look at this wonderful definition of the photobooth by members of the surrealist movement in the December 15, 1928 issue of Variétés: Revue mensuelle illustrée de l’esprit contemporain (which I unfortunately can’t find online – it’s quoted on page 92 of Pellicer’s book:

The Photomaton is an automatic device that provides you, in exchange for a five-france token, with a strip of eight attitudes caught in photographs. Photomaton, I’ve been seen, you’ve seen me, I’ve often seen myself. There are fanatics who collect hundreds of their ‘expressions’. It is a system of psychoanalysis via image. The first strip surprises you as you struggle to find the individual you always believed yourself to be. After the second strip, and throughout all the many strips that follow, while you may do your best to play the superior individual, the original type, the dark fascinating one, or the monkey, none of the resulting visions will fully correspond to what you want to see in yourself.

Bridgette Reed’s Pinterest board of photo booth images has a lot more examples. You can also browse the PDFs of La Revolution Surrealiste beautifully digitized by La biblioteque française – in the last issue, in 1929, Magritte’s painting “je ne void pas la cachée dans la forêt” is framed by photo booth portraits of 16 male surrealists with their eyes closed, all presumably dreaming of the naked woman in Magritte’s painting.

The surrealists were of course fascinated by automatic art, and as Priscilla Frank writes in commentary on an exhibition of photo booth art in Switzerland a couple of years ago,

it makes sense that surrealists would be entranced by the photo booth, an automaton that operated independently of human consciousness or human hands. Even the subjects were barely in control of their position, those photo flashes come too fast. The resulting images are pure, independent imaging; the subject is caught in limbo between pose and natural stance. In the endless stream of images, strip after strip, the people themselves lose their humanity and begin to look like automatic images as well.

Of course, if we’re comparing photobooth portraits to today’s selfies, we should be looking not so much at artistic use as at ordinary peoples’ self-portraits. But somehow I was even more fascinated by the photos of celebrities I found on Pinterest boards like Lucia Pena Sota’s FotoMatones. Oh, some of them are polished and glamorous, but many have that searching look that I see in the mirror when I gaze at my own face, or in the selfies I delete shortly after taking them. Or maybe they’re just practicing. After all, they only get a few goes with a photo booth, it’s not like a digital camera where you can shoot a hundred selfies and delete ninety-nine of them.

Related

Discover more from Jill Walker Rettberg

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.